Sustainability has transitioned from a peripheral CSR initiative to a core pillar of industrial strategy. For manufacturers, pressure now comes from every direction: net-zero commitments, ESG disclosures, customer expectations, and tightening regulatory scrutiny are no longer optional topics but are permanent fixtures in the boardroom.

Yet despite this increased attention, a strategic blind spot remains. Many sustainability strategies are still narrowly concentrated on the front end of the value chain in product design and manufacturing, while paying far less attention to how those products live, operate, and ultimately fail in the real world.

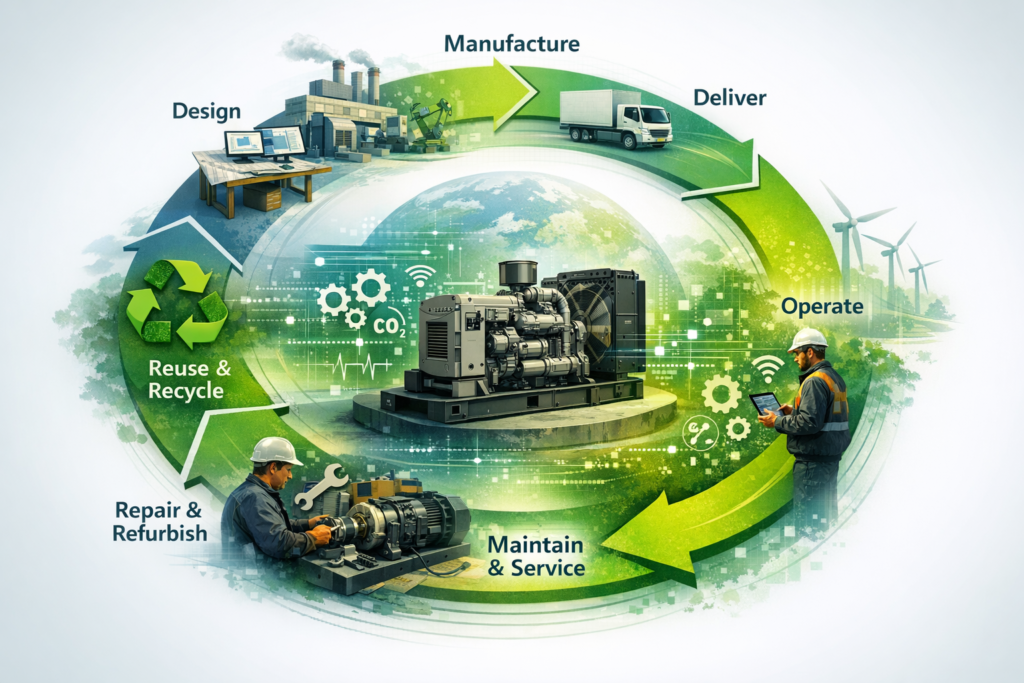

To close this gap, leaders must look beyond the factory floor and toward the full product lifecycle. Aftersales already plays a critical role in revenue and margin performance. What is less recognized is that service execution also determines the majority of a product’s environmental impact. When viewed through a lifecycle lens, aftersales becomes one of the most powerful yet the most underleveraged levers for sustainability, customer value, and long-term profitability.

Understanding Sustainability in Manufacturing: A Lifecycle Perspective

In a manufacturing context, sustainability is fundamentally about reducing the total lifecycle impact of a product across emissions, material consumption, waste, and regulatory risk, while continuing to deliver economic value. It is not limited to greener factories or renewable energy adoption. Instead, it spans the entire value chain, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal.

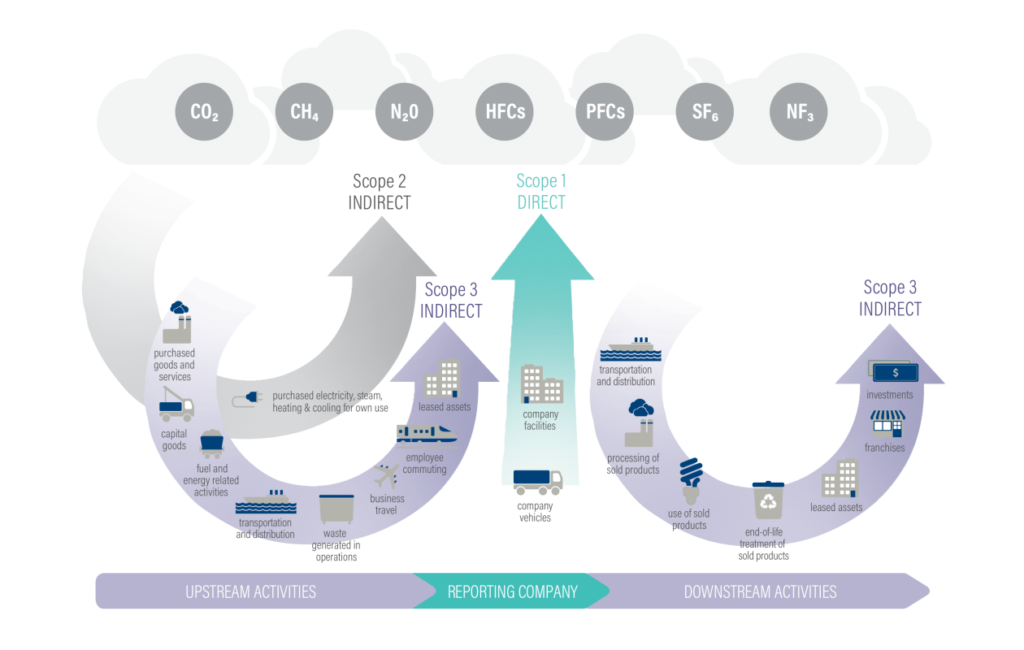

To structure this complexity, sustainability reporting relies on three categories of emissions. Scope 1 includes direct emissions from owned sources such as factories or company-owned service vehicles. Scope 2 covers indirect emissions from purchased energy like electricity and heating. Scope 3 encompasses all other value-chain emissions, including supplier activities, logistics, product use, maintenance, spare parts, and disposal.

For most industrial and automotive manufacturers, Scope 3 is by far the largest category. McKinsey estimates that Scope 3 emissions account for at least 70% of total emissions in many industrial sectors.

This distinction matters because aftersales sits squarely within Scope 3. How assets are maintained, repaired, refurbished, and replaced over time has a far greater impact on sustainability outcomes than most factory-level optimizations. In other words, sustainability is not decided at the moment of production, it is decided over the years of operation that follow.

Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol (WRI)

The Current State: Overcoming “Green” Myopia

Most sustainability initiatives in manufacturing today focus on the “birth” of the product. Organizations invest heavily in decarbonizing factories, transitioning to renewable energy, and reducing production waste. These Scope 1 and Scope 2 initiatives are necessary, measurable, and often the fastest way to demonstrate progress against climate targets.

However, this focus also creates a form of green myopia. Leadership teams optimize the manufacturing phase, often only a fraction of the total lifecycle impact, while paying far less attention to the operational life of the asset. Questions around longevity, repairability, failure prevention, and reuse rarely feature prominently in sustainability strategies.

The result is a sustainability narrative that looks robust on paper but addresses only the tip of the iceberg. Products may be manufactured more efficiently, but they are not always designed, serviced, or supported in ways that maximize useful life.

For the modern executive, the insight is simple and uncomfortable: organizations are getting better at building greener products, but they are not yet strategically focused on keeping those products running longer.

The 80/20 Rule of Sustainability Impact

To understand why aftersales matters so deeply, it is necessary to look at where emissions actually occur. A growing body of research suggests that for complex industrial equipment, 60–80% of total lifecycle emissions are generated after the product leaves the factory gate, during its operational life.

The European Commission’s Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) framework reinforces this lifecycle view, emphasizing that energy use, maintenance activities, and replacement cycles often dominate total environmental impact.

This operational impact largely falls under Scope 3 emissions, which encompass everything from spare-parts manufacturing and logistics to field service travel and end-of-life handling. When an asset fails prematurely or operates inefficiently, it triggers a carbon-intensive chain reaction: emergency logistics, expedited part production, and the disposal of high-value materials that still had usable life remaining.

Viewed through this 80/20 lens, aftersales is no longer a downstream support function. It becomes the primary engine through which lifecycle sustainability is either eroded or preserved.

Aftersales as a Strategic Sustainability Lever

Aftersales sits at a unique intersection of operations, customer experience, and lifecycle impact. Every service decision, whether to repair or replace, dispatch a technician or resolve remotely, refurbish a component or scrap it, has direct implications for emissions, material use, and asset longevity.

Yet in most organizations, these decisions are optimized narrowly for efficiency and cost. Sustainability benefits emerge as a by-product of good service execution rather than as an explicit objective. This is not a failure of service organizations; it is a reflection of how sustainability is currently governed.

To unlock aftersales as a true sustainability lever, leaders must first recognize how service execution already shapes outcomes and then understand why those outcomes remain invisible at a strategic level.

How Aftersales Already Contributes (Quietly)

Aftersales organizations already reduce environmental impact in tangible ways. Predictive maintenance prevents cascading failures that lead to premature replacement. Remote diagnostics and software-based fixes eliminate unnecessary travel. Refurbished and remanufactured components reduce demand for virgin materials and energy-intensive production.

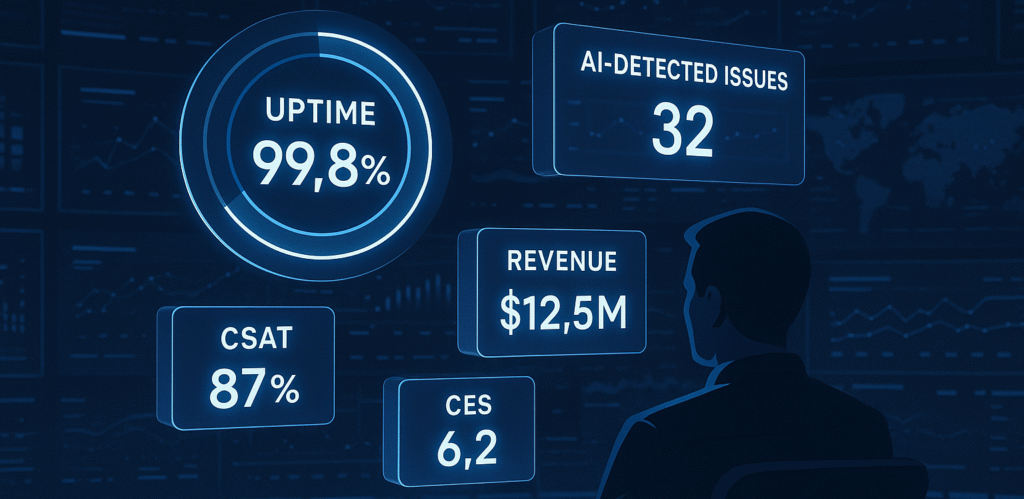

Each of these actions directly reduces Scope 3 emissions by extending asset life and avoiding carbon-heavy replacement cycles. However, these contributions are rarely described in sustainability terms. They are justified through traditional service metrics such as uptime, warranty cost, or service margin.

As a result, sustainability value exists but it remains implicit, unmeasured, and disconnected from enterprise sustainability strategy.

The Data Gap: Turning Sustainability from Abstract to Operational

One of the biggest challenges in sustainability is measurement, particularly for Scope 3 emissions. Deloitte notes that many organizations still rely on industry averages and proxy data due to limited operational visibility.

Aftersales data changes this equation. Installed base records, service histories, failure patterns, and repair-versus-replace decisions reflect actual operational behavior. When connected and analyzed, this data enables organizations to quantify avoided emissions, material savings, and lifecycle extension with far greater precision.

Without service data, sustainability remains an abstract reporting exercise. With it, sustainability becomes a manageable, optimizable outcome of service execution.

CFO’s Corner: The Economics of Longevity

Sustainability in aftersales is not a cost, it is an economics play.

- Refurbished vs. new components often require significantly less material and energy to produce, while commanding strong margins when offered as certified alternatives.

- Lifecycle-focused service models increase customer retention by aligning OEM incentives with asset longevity rather than transactional replacement.

- Predict-and-preserve approaches improve capital efficiency by reducing inventory obsolescence, emergency logistics, and unplanned service costs.

When asset life extension becomes a design principle rather than an exception, sustainability and EBITDA move in the same direction.

The shift from traditional aftersales to a lifecycle-led model is not cosmetic. It fundamentally changes how organizations measure success, make decisions, and deliver value.

| Dimension | Traditional Aftersales Mindset | Lifecycle-Led Aftersales Mindset |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Optimize individual service events and part sales. | Optimize asset life, utility, and total value delivered. |

| Primary Objective | Restore uptime as quickly as possible. | Extend asset life while sustaining uptime. |

| Success Metrics | MTTR, FTFR, service margin. | Asset life extension, avoided replacement, service margin. |

| Repair vs Replace | Replace when faster or operationally simpler. | Repair-first and refurb-first by default. |

| Role of Data | Reactive troubleshooting and fault resolution. | Predictive, lifecycle-level decision optimization. |

| Sustainability View | Managed separately through ESG reporting. | Embedded directly into service execution. |

| Scope 3 Impact | Estimated using industry averages and proxies. | Quantified through actual service actions. |

| Customer Experience | Minimize downtime during failures. | Minimize disruption and total cost of ownership. |

| Regulatory Readiness | Respond to compliance requirements after the fact. | Designed for right-to-repair and CSRD from the start. |

| Role of Aftersales | Revenue engine. | Lifecycle steward and revenue engine. |

Driving Strategic Advantage Through Sustainability

When sustainability is intentionally embedded into aftersales, it stops being a compliance obligation and becomes a source of competitive advantage. This advantage materializes across three dimensions: customer experience, commercial innovation, and governance readiness.

Customer Experience Advantage

In aftersales, sustainability and customer experience are often aligned. Repair-first and refurb-first approaches reduce the total cost of ownership, particularly in automotive and industrial environments where replacement is expensive and disruptive. Faster resolutions, fewer failures, and longer asset life translate directly into higher satisfaction and trust.

Customers may not explicitly ask for lower emissions, but they consistently value reliability, continuity of operations, and cost predictability. Lifecycle-focused service strategies deliver all three, while simultaneously reducing environmental impact.

Commercial and Revenue Advantage

Sustainability also enables new commercial models. Many organizations are moving toward lifecycle- and outcome-based contracts, where revenue is tied to uptime, availability, or asset performance rather than individual service events.

In these models, extending asset life is no longer just environmentally sound, it is economically essential. The more efficiently and sustainably an organization keeps an asset running, the more profitable the service relationship becomes. Sustainability becomes a precondition for scalable, high-margin service growth, not a constraint.

Governance and Risk Advantage

Embedding sustainability into service execution also strengthens governance. Regulatory frameworks such as the EU CSRD increasingly require granular, auditable evidence of lifecycle impact. Service data provides that evidence.

Organizations that can trace sustainability outcomes back to operational decisions reduce reporting risk, improve audit readiness, and increase credibility with regulators and customers alike.

Turning “Right to Repair” from Pressure into Advantage

Right-to-Repair legislation is gaining momentum across the US and Europe, reshaping expectations around product longevity, repairability, and access to parts. For many manufacturers, this shift is perceived primarily as a compliance challenge or a threat to proprietary service revenue.

Forward-thinking organizations see it differently. Instead of resisting repair, they are positioning themselves as the most trusted enabler of it. By offering certified refurbished parts, repair intelligence, and digital service guidance, OEMs can make repair easier, safer, and more reliable than replacement.

This approach aligns regulatory compliance with customer expectations for affordability and longevity, while reinforcing the OEM’s role as lifecycle steward of the asset. In doing so, manufacturers transform regulatory pressure into a defensible service position, one that competitors and third-party providers struggle to replicate.

What Leaders Should Change Next

Activating sustainability through aftersales does not require a wholesale transformation. It requires a shift in how service performance is framed and governed. Installed base and service data must be treated as sustainability assets, not just operational inputs.

Repair-versus-replace decisions should be made visible and intentional. Remote-first and predictive approaches should be encouraged not only for efficiency, but for their lifecycle impact. Most importantly, service execution must be connected back to product design, ensuring that recurring field failures are designed out of the next generation.

The manufacturers that lead in sustainability will not be those with the boldest pledges, but those that quietly, and consistently extend asset life through disciplined aftersales execution.